Key fobs have gradually shifted from simple convenience accessories into essential components within modern vehicle communication networks. Early implementations offered only remote locking and unlocking, but current designs operate as wireless authentication devices that interface directly with a vehicle’s electronic control units. These systems form part of a wider ecosystem of onboard electronics used in diagnostics, access control, and fleet operations. Within AutoPi, the topic arises frequently when assisting companies that operate mixed fleets or prototype vehicles, since understanding how a fob communicates with the vehicle is an important step when planning access, monitoring, or automated control workflows.

Over time, projects involving key fob behavior have revealed how much variation exists across manufacturers. Some OEMs rely on low-frequency wake-up signals paired with ultra-high-frequency authentication bursts, while others integrate with CAN-based immobilizer modules or gateway-controlled access routines. These differences influence how a system behaves in proximity scenarios and how data flows internally. The following sections outline the structure, operation principles, and usage patterns of key fobs as they appear in contemporary passenger cars and commercial vehicles.

A broad overview of key fob evolution, hardware components, and communication layers is included to provide context for later sections on troubleshooting, maintenance, and integration with telematics tools. The information aligns with current industry practices used across brands such as Volkswagen, Toyota, BMW, and various heavy-duty manufacturers that rely on standardized CAN gateways.

What Is a Key Fob?

A key fob is an electronic access device designed to authenticate a user and trigger specific functions in a vehicle. Early generations from the 1980s used infrared transmitters with simple rolling codes. Later systems—particularly after 2005—shifted toward RF-based communication combined with encrypted authentication sequences. A key fob typically interacts with modules responsible for central locking, immobilizer validation, and in some vehicles, ignition authorization.

The physical appearance has also changed. Traditional metal keys gradually merged with embedded RFID transponders, then into compact electronic units, and in recent years into card-shaped devices or smartphone-based virtual keys. The progression follows trends from both security requirements and increasing integration with digital vehicle architectures.

The core technology now commonly relies on RFID, low-frequency wake signals (typically around 125 kHz), and ultra-high-frequency commands (315 MHz or 433 MHz, with some regions using 868 MHz). These signals interact with the vehicle’s access modules, sometimes routed through gateway ECUs that simultaneously manage diagnostics, telematics, and CAN bus communication.

Systems offering keyless entry or passive entry further extend these principles by continuously monitoring for proximity, using received signal strength and challenge-response authentication to confirm legitimacy. Such features have become standard in a wide range of vehicles, including commercial fleets.

What Does “Key Fob” Stand For?

The word “fob” historically referred to a small pocket or chain used for carrying valuables. In automotive terminology it simply designates a compact handheld electronic device used for access control. The meaning aligns with earlier security fobs used in hotels and industrial facilities before automotive applications became common.

Types of Car Key Fobs

Several categories of key fobs coexist in current production vehicles:

-

Standard fobs: Basic lock, unlock, and trunk-release functionality with RF signaling.

-

Smart fobs: Integrated with push-button start systems, used for immobilizer authentication.

-

Proximity fobs: Passive entry and passive start, based on LF activation and UHF challenge-response.

How Key Fobs Work

A key fob operates through a sequence of encoded transmissions interpreted by the vehicle’s authentication hardware. These processes rely on short-range wireless signaling, combined with stored cryptographic material. Although the device appears simple externally, its internal components support multiple communication layers used for access authorization.

Internally, most fobs contain:

A microcontroller storing cryptographic keys and control logic.

A lithium coin cell battery, typically CR2032 or CR2450, providing stable long-term power.

An RF transmitter for command bursts, and sometimes an LF coil for passive detection.

When a button is pressed, the microcontroller generates a rolling or encrypted code. This is transmitted over RF and received by the vehicle’s antenna network. The vehicle compares the received code to its stored synchronization window, then authorizes or rejects the action. Many implementations rely on proprietary authentication protocols, though certain principles resemble those used in industrial RFID systems.

A simplified sequence:

Input triggers the microcontroller.

An encoded packet is generated based on synchronized keys.

The RF transmitter emits the packet.

The vehicle’s receiver interprets the signal.

The code is verified and validated.

The requested action is executed via body control modules or gateway routines.

These operations occur within milliseconds, coordinated through internal CAN, LIN, or FlexRay messages depending on the vehicle architecture. Because key fobs interact indirectly with core vehicle networks, tools such as automotive data loggers are often valuable for diagnosing access-related issues.

Uses of Key Fobs

Key fobs form an integral part of the user access layer in vehicle electronics. Their functions extend into areas related to comfort, security, and operational control. The internal vehicle network processes these commands through distributed modules, allowing features such as remote locking, ignition authorization, or configurable driver profiles.

Keyless Entry

Keyless entry systems rely on encrypted RF commands. Body control modules interpret these commands and dispatch necessary CAN frames to actuators. This architecture eliminates mechanical key use in most passenger vehicles and supports central locking across multiple doors.

Keyless Ignition

Push-button start systems validate fob presence through LF/UHF interrogation before allowing ignition. The signal is forwarded to immobilizer modules, which often communicate over CAN or secure in-vehicle networks. These systems replaced mechanical tumblers in many vehicles after 2010.

Remote Start

Remote start allows the engine or HVAC system to begin operating before entering the vehicle. This is common in colder regions, where preheating reduces engine stress and improves defrosting performance.

Trunk Release

Remote trunk release uses single-function RF commands, routed through central locking modules. It provides quick access without requiring physical contact with the vehicle.

Panic Alarm

Panic buttons activate the acoustic alarm. This function uses immediate-priority RF signaling that bypasses certain debounce checks in the body control module.

Driver Profiles

Some fobs store profile identifiers used by vehicles to adjust seat position, mirrors, or climate settings. The mapping between fob ID and stored profile is usually handled by the central gateway.

Maintaining a Key Fob

Key fobs typically operate for years with minimal issues, though environmental conditions and battery life influence reliability. Coin cell batteries used in many fobs can last from three to eight years, though some users report even longer intervals depending on RF transmission frequency and standby current.

Battery Replacement

Typical replacement steps include opening the casing, removing the battery, inserting a new one in the correct orientation, and reassembling the housing. Proper contact alignment ensures consistent RF output.

When Replacement Is Needed

Fobs exposed to moisture, heavy impact, or internal PCB damage may require replacement. Sync loss or repeated RF transmission failure may also indicate internal component aging.

Cost Considerations

Replacement costs vary widely between OEMs. Basic RF fobs are relatively inexpensive, while advanced proximity fobs can be costly due to the requirement for immobilizer reprogramming and secure key provisioning.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Wireless performance issues may stem from interference, degraded internal components, or problems within the vehicle’s receiving hardware. Interference often originates from crowded RF environments or metallic enclosures.

Signal Interference

Avoid strong electromagnetic sources.

Try repositioning the fob for improved line-of-sight conditions.

Confirm that vehicle antennas are not obstructed.

Physical Damage

Inspect the casing and internal PCB.

Remove moisture and allow sufficient drying time.

Replace the fob if necessary.

Security Concerns

Relay attacks have been documented on passive entry systems, where attackers extend LF or UHF ranges artificially. Faraday pouches, keyless-entry disabling modes, and OTA firmware updates from OEMs reduce such risks.

Preventive Measures

Periodic function checks.

Dry, protected storage.

Professional diagnostics for persistent behavior.

Advanced issues sometimes trace back to gateway modules, receivers, or CAN messaging faults. In such cases, tools like the AutoPi CAN-FD Pro provide insight into low-level communication on CAN, CAN-FD, and LIN networks.

The AutoPi CAN-FD Pro offers detailed access to vehicle communication channels and is commonly used for debugging access-related irregularities within prototype or fleet environments.

The Future of Car Key Fobs

Advancements in vehicle electronics are influencing how key fobs evolve. Increasing integration with digital ecosystems, cloud management platforms, and secure authentication protocols will likely shape future systems.

Biometric Authentication

Research prototypes from several OEMs include fingerprint readers embedded into fobs. This reduces unauthorized usage and links driver identity directly to access control.

Smartphone Integration

Virtual keys stored in secure smartphone environments already appear in brands like Hyundai, BMW, and Tesla. Communication typically uses Bluetooth Low Energy, NFC, or UWB. The trend suggests a gradual shift away from physical fobs in certain markets.

Connectivity Expansion

Future vehicles may link access control to home automation or enterprise fleet platforms, enabling coordination with security systems or dispatch tools. These developments align with broader IoT integration trends.

Market Trends and Innovations

Security updates with stronger encryption and rolling-code algorithms.

Energy-efficient designs using lower standby consumption.

Greater customization for multi-driver vehicles.

Fob-related functionality often becomes more important when deploying connected fleets. Early prototype projects typically reveal how varied OEM implementations are, so reliable access logging and control mechanisms are valuable during both development and field testing.

Going Keyless with AutoPi

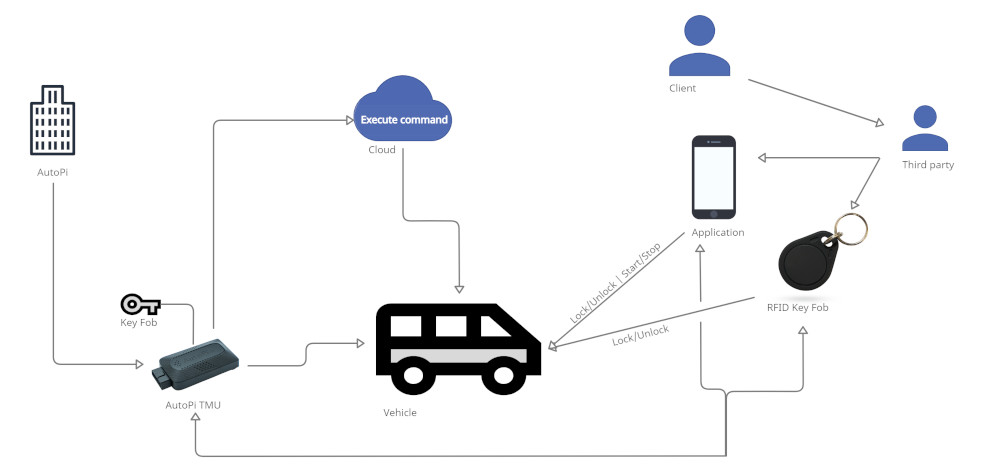

Keyless systems in fleets often require coordinated control and auditing. The AutoPi keyless entry solution integrates access control with fleet oversight and remote operation capabilities. Vehicles can be unlocked, locked, or started through secure channels managed in the AutoPi Cloud. This is used in both rental fleets and industrial vehicle deployments.

AutoPi devices operate as communication hubs, bridging CAN bus data, remote commands, and real-time monitoring. The system relies on encrypted communication paths and can integrate with existing fleet management software or operate independently.

Key features include:

Centralized fleet control without issuing physical keys.

Remote locking, unlocking, and start authorization.

Encrypted communication channels.

Compatibility with existing management platforms.

Straightforward installation.

Conclusion

Key fobs illustrate how vehicle access systems have developed alongside broader trends in automotive electronics. Their functionality extends far beyond simple locking mechanisms and now forms part of a distributed digital infrastructure used in security, convenience, and fleet operations. These systems interact closely with in-vehicle communication networks, including CAN and CAN-FD.

Tools such as automotive data loggers support deeper insight into these interactions, particularly when diagnosing irregular behavior or planning new vehicle functions. As vehicles continue transitioning toward connected and software-defined architectures, access control mechanisms will likely follow the same trajectory.

An understanding of OBD-II PIDs, gateway behavior, and CAN message flow remains useful for technicians and developers working on modern vehicles, especially when integrating remote access or monitoring systems.