This guide gives a practical introduction to MDF4 (MF4), the ASAM measurement data format widely used for high-volume automotive logging from CAN, CAN FD, LIN, FlexRay, and ECUs. The goal is to explain how it works and why it matters for modern vehicle data pipelines.

Originating from the ASAM MCD-2 MC (ASAP2) ecosystem, MDF4 is the successor to the established MDF 3.x format. It was designed for today’s data rates and retention requirements, with a focus on long-duration logging, multi-bus support, and reliable post-processing.

The following sections break down the core concepts behind MDF4 and show how the format supports efficient, repeatable data management in automotive projects.

What is an MF4 (MDF4) file?

Measurement Data Format version 4 (MDF4) is an ASAM-standardized binary file format used to store time-series measurement data. It is widely adopted in the automotive domain for logging and managing a broad range of vehicle data efficiently.

MDF4 files typically contain signals captured from vehicle networks such as CAN, CAN FD, LIN, FlexRay and from sensors connected to Engine Control Units (ECUs). ECUs coordinate key vehicle functions, so MDF4 is often used in development, calibration, durability testing, and field data collection.

A key strength of MDF4 is that it stores both the raw sampled values and the associated metadata. This includes information required to decode and convert raw values to physical units, plus ASAM-consistent signal names and attributes. As a result, the file can be parsed and interpreted without an external configuration file if the metadata is present.

MDF4 also supports optional comments, attachments, and additional binary payloads, making it flexible enough for a wide range of test and telematics scenarios. In practice, MDF4 files act as self-contained measurement containers that are well suited for analytics, regression testing, and system monitoring across vehicle programs.

Benefits of Implementing MDF in Data Management

The Measurement Data Format, especially in the MDF 4.x series, provides a number of practical benefits when used as a standard logging and exchange format.

-

High-performance read and write access

-

MDF is designed for efficient recording and playback of large measurement sets. Its index-based structure allows fast access to signals and time ranges, which is essential for handling long test drives, bench runs, and high-frequency bus traffic without excessive I/O overhead.

-

-

Broad tool and library support

-

MDF is supported by many commercial and open tools. There are several free libraries and utilities for reading and writing MDF4. One example is MDF4-Lib, a free C++ library that implements the ASAM MDF4 standard. This ecosystem reduces integration effort and makes it easier to incorporate MDF into existing toolchains.

-

-

Interoperability across vendors

-

MDF’s wide adoption means that many logging tools, calibration systems, and analysis applications can read and write the same file format. This enables straightforward exchange of measurement data between OEMs, suppliers, and test houses without custom converters for every workflow.

-

-

Support for very large files

-

MDF 4.x supports file sizes up to 264 bytes. This makes it suitable for long-duration logging campaigns and high-bandwidth sources without needing to split data into many small files, simplifying indexing and file management.

-

-

Built-in compression options

-

MDF 4.1 introduced payload compression for measurement data. Compression reduces storage requirements and can lower server and network costs, which is particularly valuable when uploading logs over cellular networks such as 3G, 4G, or 5G from vehicles in the field.

-

-

Backward compatibility with earlier generations

-

MDF 4.x can represent data in ways that maintain compatibility with legacy MDF usage, including pre-sorted measurement files. This reduces migration friction and avoids expensive post-processing steps for sorting large datasets at the end of a measurement run.

-

-

Extended support for bus and message logging

-

With MDF 4.1, the format can store both raw bus messages and derived classification results for buses such as CAN, LIN, FlexRay and Automotive Ethernet. This allows signal-oriented and message-oriented analysis to be performed from the same file without redundant logging.

-

Overall, MDF provides a combination of performance, scalability, and compatibility. Together with compression and rich bus support, this makes MDF a strong foundation for standardized data management in automotive development and operations.

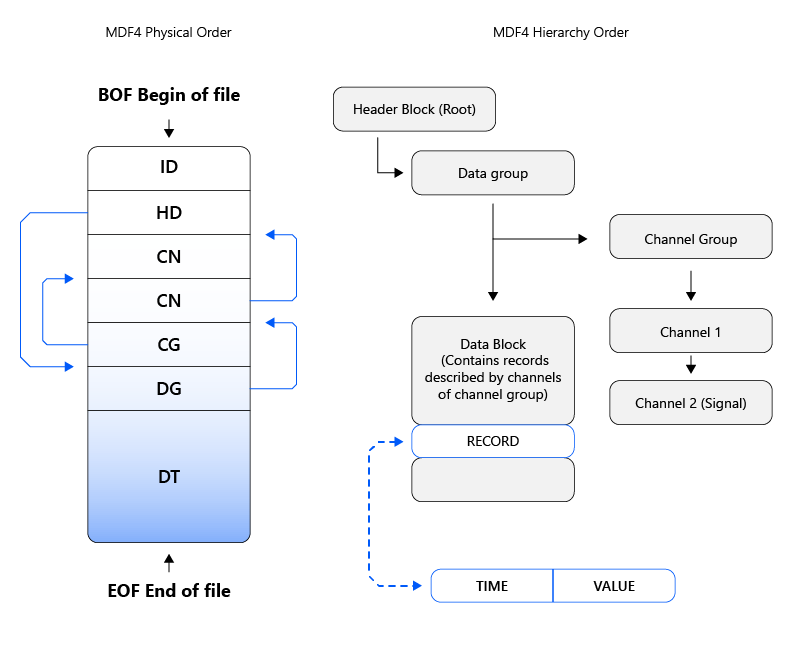

The File Structure of MDF4 Files: The Block Hierarchy

MDF4 files are organized as a hierarchy of binary blocks. Each block type has a defined purpose and structure, and blocks link to each other via offsets. Understanding this hierarchy is important when parsing MDF4 or when designing tools that operate on it directly.

Files with the *.mf4 extension follow a consistent layout based on these blocks. Some appear exactly once at fixed locations (such as the identification block), while others are repeated for each data group, channel group, or channel.

Core blocks in MDF4 include:

-

Identification Block (ID): The ID block uniquely identifies the file as MDF and specifies the MDF version. In MDF4 it has a fixed size and position and appears exactly once at the beginning of the file.

-

Header Block (HD): The HD block is the root of the file hierarchy. It contains global information about the measurement and links to the top-level data groups and other structural elements.

-

Channel Group Block (CG): The CG block defines how channels that are sampled together are arranged in records. It describes the layout for one group of jointly measured channels within a data group.

-

Data Group Block (DG): A DG block describes a logical measurement run or data set. It references one or more channel groups and the corresponding data blocks that contain the actual samples.

-

Data Block (DT): DT blocks hold the actual data records with signal values (for example, CAN frames or sampled sensor values). Together with CG and CN blocks they define how log data is stored and parsed.

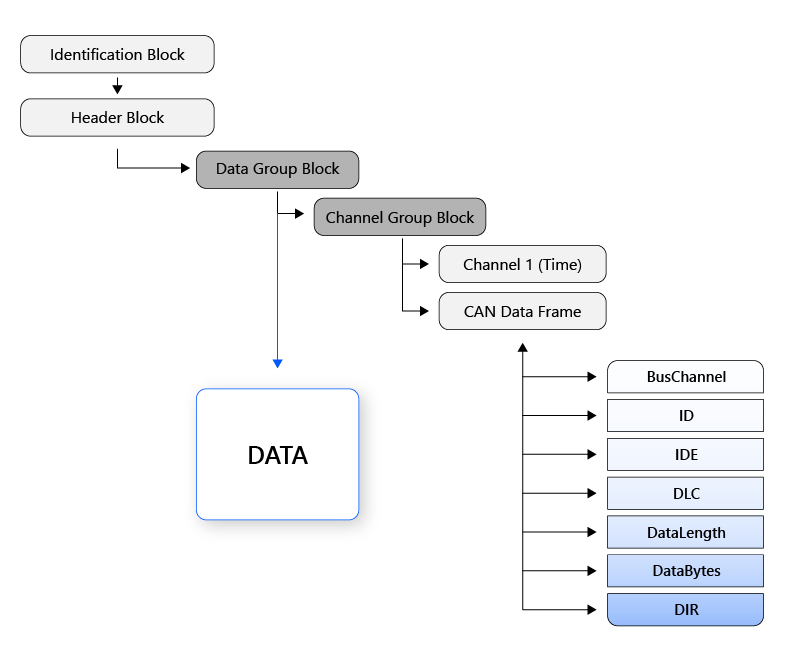

MDF4 CAN Data Frame: MDF4 defines a dedicated structure for CAN frame data, split into multiple subchannels (e.g., ID, DLC, direction, payload bytes). This layout is optimized to store both raw frames and derived signals efficiently within the same file.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| BusChannel | Logical grouping of bus traffic (for example CAN or LIN channel) used to separate messages from different physical or logical buses in the same file. |

| A CAN message (frame) typically consists of an identifier (ID), which encodes priority and addressing, and up to eight data bytes for classical CAN (more for CAN FD). | |

| E | Frame type indicator (standard or extended ID format). |

| DLC | CAN frame Data Length Code as transmitted on the bus. |

| DataLength | Actual number of payload bytes (may differ from DLC for CAN FD). |

| DataBytes | The payload bytes of the CAN frame. |

| DIR | Direction flag (received or transmitted frame). |

Because MDF4 enforces a clear block structure and supports rich metadata, it integrates well with cloud analytics and telematics workflows. It can represent data from CAN, CAN FD, LIN, J1939, OBD2, CANopen, and other protocols within a single, consistent container.

In-Depth Look at the Technical Composition of MDF Blocks

The table below summarizes the most important MDF4 block types and their purpose. Together they describe file metadata, measurement structure, channels, conversions, and the actual signal data.

| Abbreviation | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ID | Identification block | Marks the file as MDF and encodes version and byte order. |

| HD | Header block | Global description of the measurement file and entry point to the hierarchy. |

| MD | Metadata block | Container for an XML document (e.g., ASAM metadata) of variable length. |

| TX | Text block | Stores human-readable strings such as comments or descriptions. |

| FH | File history block | Records changes applied to the MDF file over its lifecycle. |

| CH | Channel hierarchy block | Defines logical hierarchies and grouping relationships between channels. |

| AT | Attachment block | Stores binary attachments or references to external files. |

| EV | Event block | Describes events such as triggers, markers, or annotations in time. |

| DG | Data group block | Defines a measurement data set and references its channel groups and data blocks. |

| CG | Channel group block | Groups channels that are sampled together into one record layout. |

| SI | Source information block | Describes the acquisition source (e.g., ECU, logger) for a channel or group. |

| CN | Channel block | Defines a single channel, its data type, bit width, and storage location in records. |

| CC | Channel conversion block | Specifies how raw values are converted to physical units (e.g., scaling and offset). |

| CA | Channel array block | Describes array-type channels and dependencies between indices and values. |

| DT | Data block | Contains records with signal values as defined by channel groups. |

| SR | Sample reduction block | Describes reduced (downsampled) signal values used for previews or overviews. |

| RD | Reduction data block | Stores sample reduction results, typically triples such as min/avg/max. |

| SD | Signal data block | Holds variable-length signal data where fixed record layouts are not used. |

| DL | Data list block | Maintains ordered references to data blocks spanning multiple segments. |

| DZ | Data zipped block | Stores compressed data sections that logically replace DT/SD/RD blocks. |

| HL | Header of list block | Header for linked lists of data blocks used in segmented recordings. |

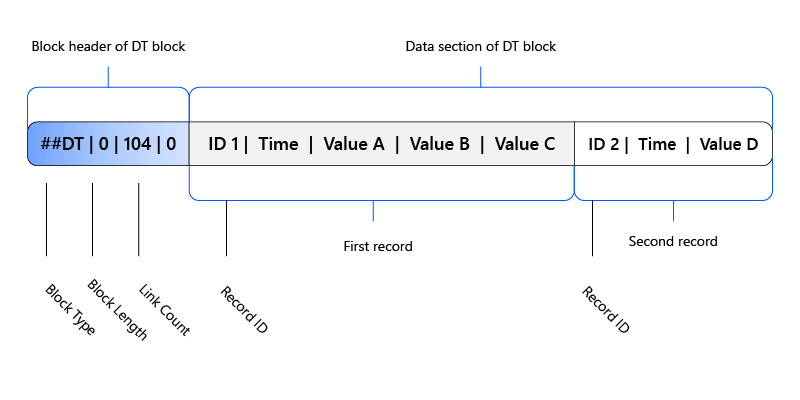

Data Block Architecture: How Record Channels Shape Structure

In MDF4, the structure of a data block is determined by the channel group that references it. Each record in a DT block corresponds to one sampling step and contains the values for all channels defined in the associated channel group.

Because these values are written synchronously, records are time-consistent and aligned. Data blocks do not include link sections; records are stored back-to-back without gaps. This design simplifies indexing and improves sequential read performance during analysis.

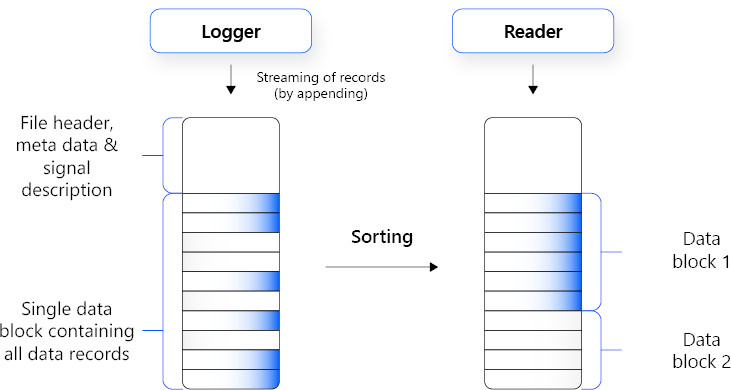

Sorted vs. Unsorted MDF Files

The way records are organized within MDF data groups can differ before and after sorting. If a data group is linked to a single child channel group, all records inside the corresponding DT blocks follow one fixed layout.

For sorted data groups, MDF allows dropping the record ID field because records are already ordered by time. This enables faster, index-based access, as the position of a record can be derived from time and record size.

In contrast, unsorted MDF files can contain records from multiple sources or unsynchronized segments. Many tools sort these files during or before analysis. Sorting in MDF is a lossless operation that reorders records without changing their content, eliminating the need to buffer data extensively during live recording.

Sorting improves query performance and makes downstream processing more predictable, while preserving the full fidelity of the original measurement.

The Evolution of MDF

MDF has evolved alongside increasing requirements for ECU development, calibration, and in-vehicle logging. It was introduced to provide a standardized, reliable way to store measurement data across tools and projects.

Key milestones in the MDF evolution include:

-

Initial MDF versions were introduced in the 1990s and quickly became a standard for handling ECU and vehicle measurement data.

-

The format was tailored for complex tasks such as ECU development, calibration, and system-level testing.

-

MDF 4.0, released by ASAM, removed earlier file size limits and introduced a more flexible block structure.

-

MDF 4.1 added payload compression and support for variable-length data, improving efficiency for modern logging use cases.

-

MDF 4.2.0, the latest revision, extended layout options and signal handling to better support complex multi-bus and multi-rate measurements.

-

The ongoing evolution of MDF reflects the increasing data volumes and complexity in automotive programs.

-

The standard has been shaped by collaboration between OEMs, tool vendors, and engineering teams, ensuring that it remains practical for day-to-day use.